Runbook doctors

During 2019 we introduced a new runbook authoring standard at the FT, called RUNBOOK.md. This is the tumultuous story of its birth.

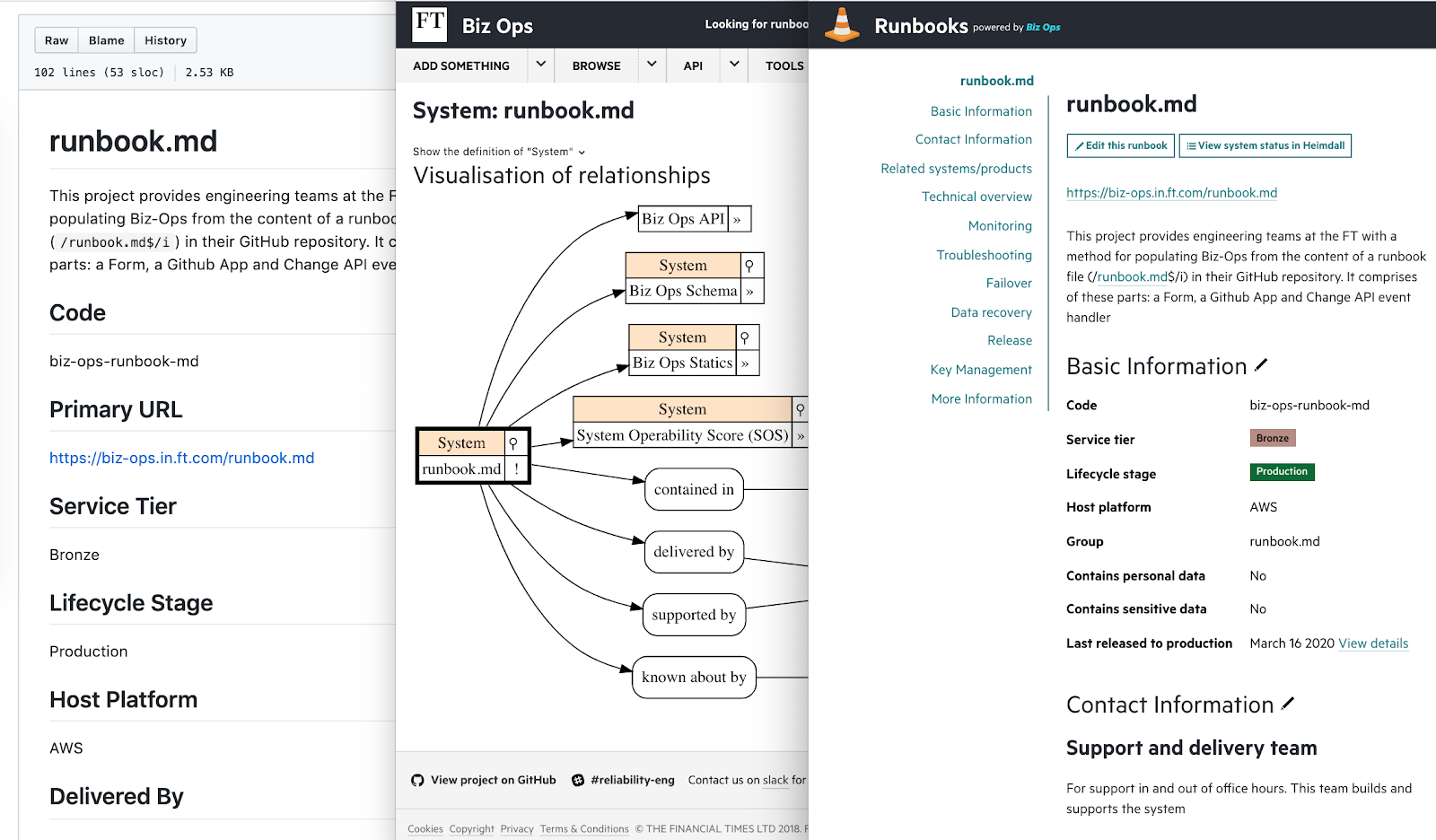

Caption: Screenshots of a RUNBOOK.md file, the graph of data it generates, and the finished static runbook.

What is a runbook?

A runbook is a very specific type of technical documentation. With as few distractions as possible, it should tell somebody who is on call what they can do to restore (or at least improve) a service that’s not in a healthy state, and details of how to escalate if they are unable to fix the problem.

Systems will break, given enough time, so documenting how to recover when that happens is a vital part of achieving our reliability goals. In early 2019 many runbooks were either incomplete or out of date, so a big focus for the FT’s Reliability Engineering team was to improve this situation.

I’ll take you through some of the key points of the project, sharing what we did and what we learned along the way.

1. Structured, interconnected data makes for a good runbook

When we spoke to our Operations Support team — who watch over our tech 24/7 — about which information should be in a good runbook, it tended to fall into 3 categories:

-

Relationships between things, e.g. which systems depend on which others & which team is responsible for supporting a system

-

Simple multiple choice or boolean properties indicating things such as whether a system contains personal data, or whether it has an automated rollback process

-

Longer free text fields containing specific troubleshooting information and additional detail about types 1 and 2

Storing runbook data in a format that captured this structure formed the basis of our SOS project to gamify runbook quality. Our choice of data store for runbook information — a graph database called neo4j with a GraphQL API on top of it — is flexible enough to store and expose these types of data, and our runbooks are hosted on a very reliable static site made up of HTML snapshots taken whenever the data changes.

The systems that store, edit and display this information we collectively call ‘Biz Ops’, short for ‘Business Operations’.

2. ‘Documentation as code’ has many advantages over other authoring workflows

Biz Ops has a CMS for administering the graph of data, as well as for editing the longer form technical and troubleshooting documentation. To edit a runbook, an engineer had to go to this CMS and edit the appropriate record.

There were several problems with this:

-

Editing large documents in text areas on a website is a poor authoring experience compared to, say, Google docs or your favourite desktop text editor.

-

It’s also detached from the process of making code changes; when a pull request that fundamentally changes the architecture of an application is made, we rely on the engineer to remember to head off to the Biz Ops website to update information there.

-

There’s no process or tooling to intervene and review the quality of documentation at the time of writing, or to go back and review changes at a later date.

These factors combined to leave our runbooks full of superficial, poorly structured and out of date information.

Providing the ability to author runbooks in the same repository that held a system’s source code, and coupling runbook changes to code changes, seemed like an attractive solution to all these issues, and so we kicked off a project to support this workflow.

3. Not everybody will tolerate YAML

We went through quite an extensive user research phase. This included circulating a draft proposal involving lots of YAML and a directory of markdown files. This solicited plenty of useful feedback and — more importantly — got engineers across the department engaged with the project. We followed up with a workshop to discuss requirements and brainstorm ideas for improving on the first draft.

The resulting debate uncovered some inconvenient truths (to my dismay, not everybody is a fan of YAML) but was useful for identifying areas of agreement, as well as where we would need to continue working to find consensus. It really got people thinking about what goes into a *good *runbook too — many engineers had only ever experienced bad ones.

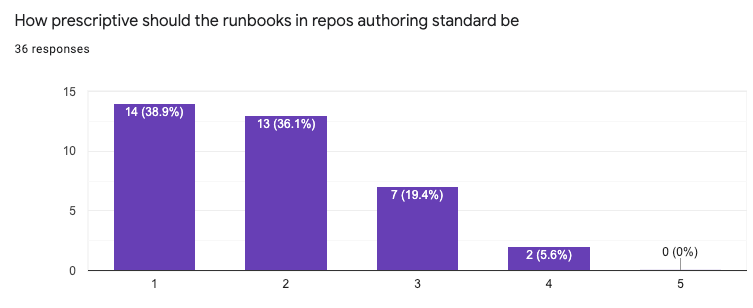

Subsequently, a survey sent around the department helped reinforce the main conclusions from the meeting; that engineers were comfortable with us releasing a strongly opinionated solution as long as it required very little effort to integrate with, and that a single markdown file was the preferred format — RUNBOOK.md was born!

Caption: Our survey showed a clear preference for a prescriptive approach (1 in this graph means “Just tell me the standard format and file structure, and I’m happy to stick to it”)

The proposal we circulated soon after — basically markdown with YAML front-matter — met with general approval so we were ready to start building the tool.

4. Who needs YAML when markdown already is a structured data format?

Our team is staffed partly by secondees, who join us for periods of 3 months from other departments. Chee Rabbits joined our team and took on the challenge of turning the RUNBOOK.md format into reality. In doing so, they injected a load of fresh ideas into our thinking.

After conducting further research into the pros and cons of variants on the proposed standard (including how the files would display in the github UI), and investigating open source tools for converting markdown into other structured data, we decided to go for a format where H1 and H2 elements in the markdown file, and the content immediately after them, are coerced into properties of a JSON object. This has the advantage that the format is semantically structured and readable as a standalone file or as data to be piped into Biz Ops and our runbooks static site.

Our tool for converting markdown to JSON, based on some yaml schema definitions, is now open sourced.

5. User research is vital, but don’t forget to use all your available data

We collaborated with the FT.com team for docs day, which involved the whole engineering team taking a day to improve their runbooks using our new RUNBOOK.md tool. In many ways it was a success but for us, the maintainers of the tool, it was a mixed blessing.

Some use cases we had thought would be quite rare turned out to be quite common. Several of the projects that were worked on that day had more than one system’s source code in a single repository and for the FT App — an enormous legacy codebase — the level of automation we’d assumed could trigger our runbook publishing didn’t quite exist.

While the user research we did was clearly valuable, and steered us away from versions of the project that would have flopped, we had unfortunately only looked at half the picture.

We had access to lots of data, in the form of thousands of git repositories and system records in Biz Ops, that would have helped us answer questions like ‘What percentage of repositories hold code for multiple systems?’.

But we didn’t even get as far as asking the questions that the data would have helped answer. Armed with the user research, we thought we had the right answers, but with any answers come unspoken assumptions; we would have done well to spend some time examining those early on.

6. Don’t just focus on what’s bad with the status quo: try to recognise what’s good too

Even for repositories that fitted the ‘single system per repo, hooked up to continuous deployment’ paradigm, there were various teething problems and unforeseen downsides to the authoring experience. For instance, in the Biz Ops CMS there is autocomplete for creating dependency relationships between systems. This is not supported in whatever text editor the RUNBOOK.md author uses. Also, our new format did not support deleting all connections to other records, and locked the data it had written so this could not be corrected in the CMS either.

Now that we recognise these disadvantages of RUNBOOK.md it’s possible to mitigate or eliminate them, but it’s always harder to retrofit things like this. A bit more analysis of what our existing solution was actually capable of and good at would have helped us address these cases earlier.

7. Serverless applications and Github Apps are hard to test and debug

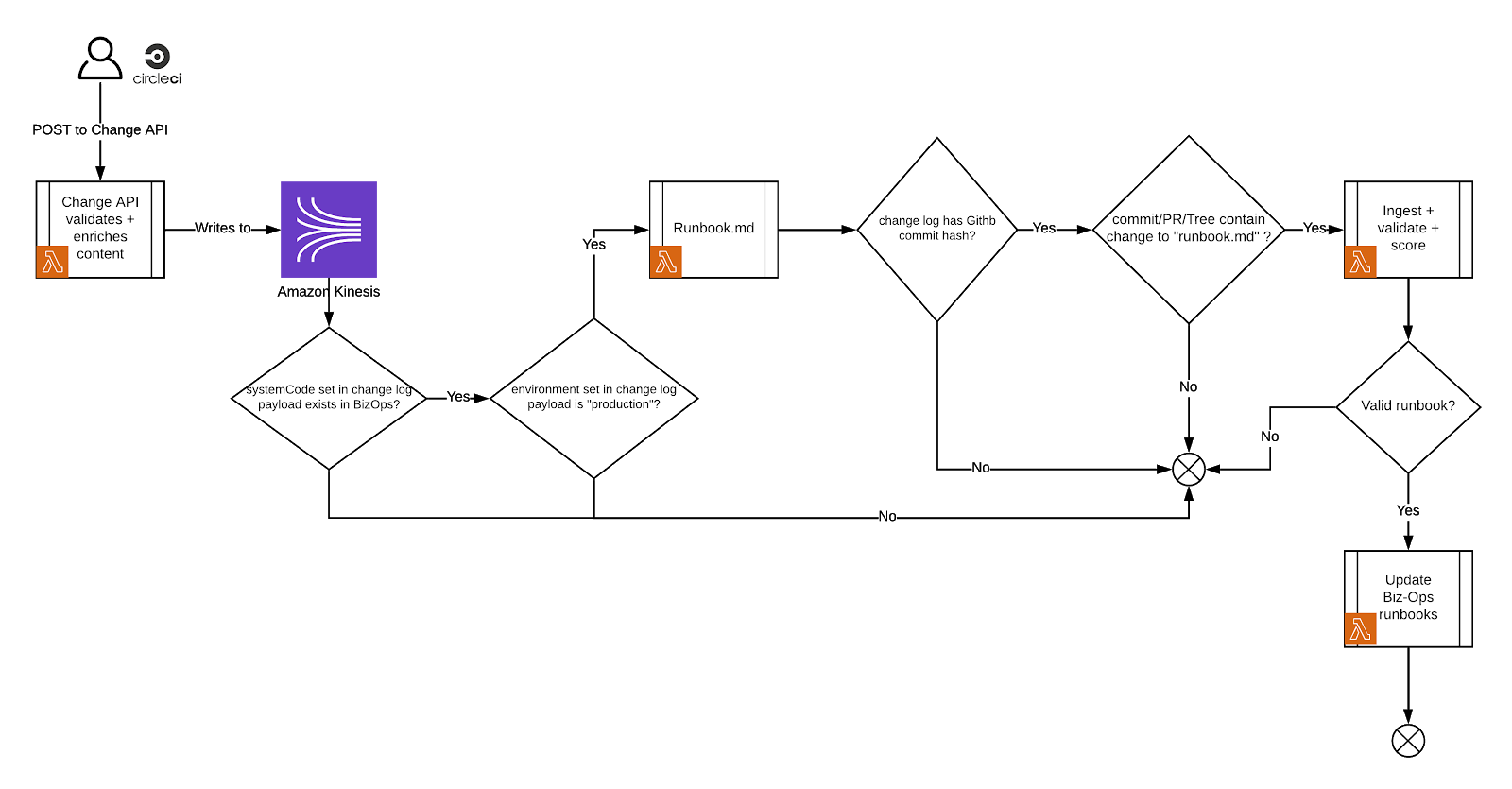

The application which controls the validation, parsing and ingestion of data from RUNBOOK.md files into Biz Ops is a suite of AWS lambda functions that listens to events published by our change log application and webhooks sent by Github.

It’s a fairly convoluted system, listening to signals and drawing data from a number of different sources. Our initial user research suggested that we only needed to support listening to Change API events, and that building a Github App to validate runbooks and leave comments on Pull Requests was nice to have, but hardly an essential part of the project.

However, if we’d done more digging into the data about deployment patterns we’d have realised that the Github app was, rather, an indispensable part of the project. We ended up having two parallel ingestion processes, with miniscule variations in behaviour and — you guessed it — bugs aplenty.

Eventually Dora was able to rearchitect in the way it probably should have been from day one (had we only looked at the data… I can’t stress this enough — look at the data before you build). The final architecture has parsing handled by the github app, and the ingestion triggers (webhooks and change logs) are relatively thin layers on top of this. But even now that the architecture is more sensible, it’s still tricky to debug and release with confidence. I think we all learned the importance of having a good local mock when building for event sources outside of your application’s control.

8. Always remember the problems you’re trying to solve

One of the problems — and arguably the most important — that this project was trying to solve was the tendency of runbooks to not get updated to keep up with the application’s code. We have plans to have more automation around code changes so that, e.g. on every pull request we automatically comment with a runbook maintenance checklist. But was there anything stopping us doing that first, before implementing the new authoring process?

It’s hard to say if such a nudging tool would be effective without a better authoring experience, but it would certainly have been quicker to implement.

So what’s next?

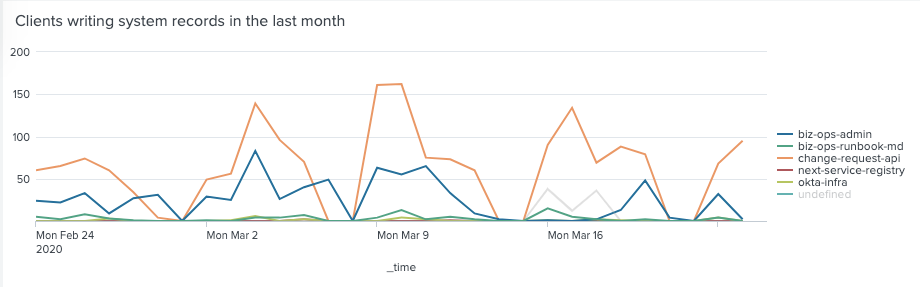

The project clearly isn’t over. There is so much more to delivering an internal product than building it. Now we’ve done the difficult engineering part — and it was difficult — we’re going to have to get on with the even more difficult cultural part. We’re collecting more metrics on what changes get made to runbooks and how, and will try different approaches to improve the numbers.

Complimenting what we’ve built so far, these might include new github apps, and slack integrations to nudge engineers towards updating more often, workshops and training to focus on more qualitative aspects of writing documentation, or maybe automating production of docs.

Whatever the project looks like, it’s been a great learning process so far — both on the engineering and product delivery sides. We’ll be measuring the results we care about, validating approaches with as little effort as possible, and making sure that we get even more value out of the efforts of our talented engineering team.

Yaffle