I don’t think I’ve ever been more grateful to have a hobby I love. Over the last few months of lockdown, birdwatching has given me many hours of soothing time outdoors, dotted with enough variety and, at times, excitement, to relieve the tedious predictability of the lockdown routine.

I’m fortunate to live within a few minutes walk or cycle of Walthamstow Wetlands and Marshes in the Lee valley. Despite being about 3 miles from central London, it’s often only the distant sight of Canary Wharf Tower on the horizon that reminds me that I’m strolling in one of the world’s great cities.

Birdwatching in this local area — “Patch birding” to use the activity’s proper name — is something I’ve done since around the time I moved to Walthamstow 2 years ago. Of late, it has increased from a once or twice weekly activity to once or twice daily.

But dreary times lie ahead.

April and May are the highlights of a “Patch birder“‘s calendar. Over the course of these two months of rising temperatures and lengthening days our summer migrants, one by one, arrive on our shores. From the first Swallow* that does not make the summer, to the relatively dawdling Spotted Flycatcher, each day can see a trickle or wave of new species arrive.

Birds that breed further north will pass through, sometimes literally flying by, other times spending a few days in a local meadow to refuel. Every now and then — if you’re lucky — a real rarity will overshoot its intended destination in another country or continent and land in your local patch, bedraggled and bemused by the hoarde of twitchers descending from around the country to ogle it.

April and May are when patch birding is at its peak, with each day’s sun rising with a twinkle in its eye that might just be the silhouete of a rare Siberian passerine.

But April and May, as of today, are over.

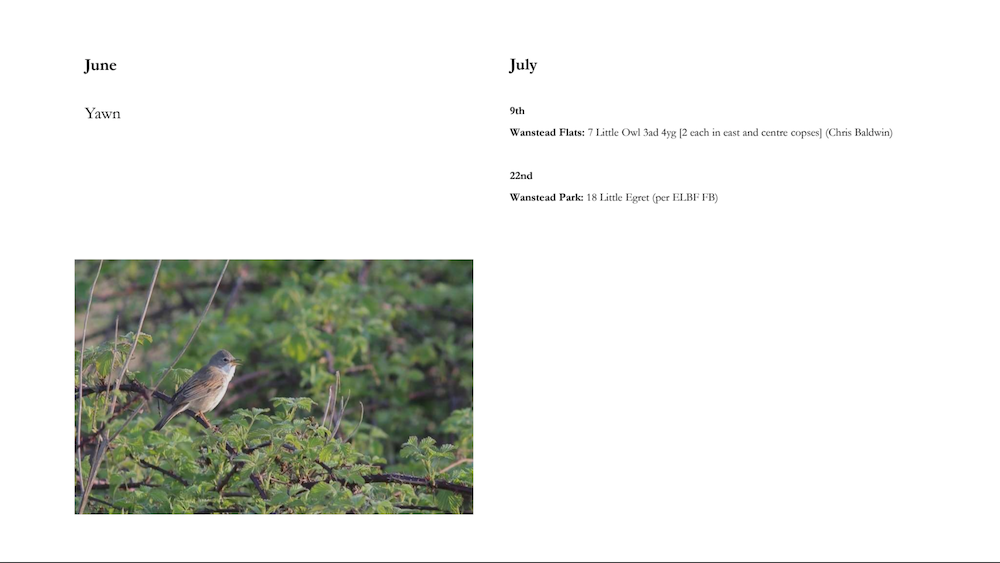

Some birdwatchers on nearby patch Wanstead Flats produce a yearly report. The entry for June merely states ‘Yawn’, and the entry for July is little better.

This tongue-in-cheek review of those months, while exaggerated, does resonate though. Normally I would just spend less time birdwatching and do something else instead until August (for many species, autumn migration starts around then), but that’s not really an option these days.

Is there something I can do to zhuzh up the whole patch birding experience during these lean summer months?

This series of blogs aims to be the answer to that question. Rather than bemoaning the lack of exciting birds on the patch, I’m going to write a new blog each day about my excursions around the reservoirs and marshes. I’ll cover the run-of-the-mill birds and other wildlfe I see, with a particular focus on a different one each time.

If I count up all the birds I am pretty much guaranteed to see locally over the next month — despite their reputation as free spirits, most birds are embarassingly parochial in their habits — it comes to 54, so there is a little excitement inherent in this challenge. To get to 61 I am going to have to see a few not quite so day-to-day things, so that’s something to look forward to.

So what’s a bird like an Osprey doing in a blog like this?

“Ospreys are mythical”, was one response to reports that one had been seen from a member of my local birding whatsapp group. They are, indeed, quiet special creatures, and I was lucky enough to be one of the people there to see it.

After a long day at work, ending with two and a half hours of meetings, I treated myself to a quick cycle over to the wetlands. I headed straight for the central path, in the hope of glimpsing one of the Spoonbills that have recently taken up semi-residence next to the heronry.

Being a permit holder gives access when the reserve is closed to the general public, and the atmosphere was beautifully calm. Swarms of midges billowed like clouds of smoke above the trees and the sun, now low in the sky, illuminated everything in a beautiful warm yellow light.

A family of Great Tit, the young with a conspicuous yellow tinge to their cheeks, were noisily feeding on caterpillars in a nearby willow, and a grumpy fisherman (I’m sure the lockdown has made them grumpier than usual) scowled his way past.

Hearing some caws overhead, I turned my bins (binoculars) to the skies to examine a few passing crows, hoping to find an errant Rook or Jackdaw — or maybe even a Raven —, but no such luck. I almost didn’t bother taking a look at a final crow chasing what looked like a large gull, but I’m very glad I did.

Ospreys are magnificent birds of prey, bigger than a Buzzard and with long wings that propel them through the air with an elegance reminiscent of a Manta Ray swimming. Illuminated by the clear late afernoon light I could pick out the detail of its plumage, right down to the yellow eye blazing through its dark chocolate mask of Zorro.

Not everybody is a birdwatcher, so not everybody will grasp just how breathtaking a moment like this is. A conservation success story, Ospreys recovered from extinction and now breed as close by as Essex (though) and, I’m proud to say, in my native Wales. Despite their recovery, they are still revered, as are many other once-rare birds of prey such as the Red Kite.

Wintering in Africa, a few Osprey are seen as they pass through London every year, but they rarely stick around for long so to see one combines both the thrilling sight of a beautiful wild creature and feeling like the lucky annointed one who is blessed with the experience.

It feels like a cheat to start a blog called “61 Boring Birds” with such an exciting scoop, but this is the joy of patch birding. I’d already decided to write a daily blog through these less-exciting months, knowing that there is always interest, beauty and pleasure to be found by sifting through the mundane and everyday. As luck would have it a nugget of gold fell right out of the pan on the first attempt.

So welcome to the 61 boring birds blog, running until the end of July. Not every day will have today’s glamour, but they will all at least, I hope, have something.

* Sand Martins actually arrive earlier, though a few hardy Swallows unbelievably now spend the winter in Britain.